Vol. 1, No. 7, Published November 4, 2015

Guest Column: Robust Housing Market Fuels Long-Distance Commuters

However, Net Economic Return is Exaggerated for Many Owners; Trend Exacerbates Traffic Congestion and Prolongs Recessions in Outlying Areas

By Joe Janczyk

While driving on the heavily congested freeway from his affordably priced home in the suburbs to his higher paying job in an urbanized area, a long distance commuter wondered why his decision to purchase a home eventually brought him so much turmoil � How did it go so wrong?

Back in 2005, with housing prices escalating rapidly, he made the decision to purchase a single-family home. However, he could only afford to purchase a home in a development fringe area. Regardless, he felt that he was living the American Dream of providing his family with homeownership and also expected an enormous equity gain. But just a few years later, in 2007, as the housing market bubble began to implode, he found his homeownership under significant duress. Many of his neighbors lost their homes in foreclosures and short sales. Although he was able to hang on, eight years later, his home is still underwater. Unable to sell his home, he continues to endure the long commute.

How did he find himself in such a situation? Here is a possible answer from an economics perspective: Renters who live in urbanized areas, which offer better employment opportunities, often decide to become long-distance commuters so that they can purchase a home when housing market conditions are robust. They are motivated by illusory extraordinary financial returns from homeownership as an investment. Therefore, they decide to undertake a lengthy daily commute, which creates higher levels of traffic congestion.

Based upon a substantial amount of research on geographical housing price patterns, a paradigm that is helpful in gaining insight into a household�s decision to engage in long-distance commuting is to financially model the activity of commuting as a �business� that involves a consideration of the relevant benefits and the costs.

- Benefits: Households living in apartments in areas where housing is comparatively expensive have an incentive to undertake long-distance commutes to lower-priced areas because it opens up the possibility of purchasing a single-family home at a significantly reduced price that they can afford. For example, a 2,000 sq.ft. new home in an urbanized area such as the City of Irvine costs about $800,000, while that same type of home approximately 40 miles away in a development fringe area such as Moreno Valley costs about $300,000. The $500,000 difference is the incentive for the household to commute from a home in the development fringe to a job in an urbanized area.

- Quantitative Costs: These costs are related to the vehicle depreciation as well as maintenance and operating costs.

- Net Economic Return: When these benefits and quantitative costs are put into a long-term financial model, the economic return under normal economic conditions is positive. In fact, under stable housing market conditions, households typically earn an implicit wage of $15 to $20 per hour for enduring the commute.

Long-distance commuters, in turn, can be partitioned into the following two categories, depending upon the housing market conditions under which the benefits are calculated:

- Stable Housing Market Conditions: The net economic return, based upon a normal appreciation rate of about 5 percent, represents a realistic expectation, and so it has a rational basis. Nevertheless, from a psychological perspective, many studies indicate that households acclimate to the happiness of owning a home in about a year. However, with regard to long-distance commuting, this activity continues to be a stressful experience.

- Robust Housing Market Conditions: The net economic return is exaggerated due to the high rates of price appreciation being built into the financial model, thereby providing the illusion of extraordinary financial returns. Consequently, households’ decisions are driven primarily by investment returns. Therefore, they do not have a long-term rational basis, since they expect that these high rates of return will continue indefinitely.

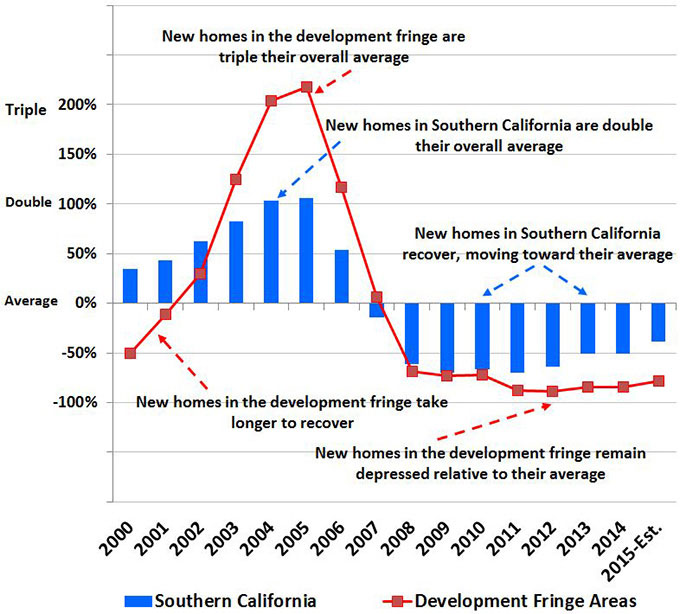

In Southern California, from 2003 through 2005, home prices increased at an annual rate of some 23 percent per year and the level of new single-family homes attained peak levels of about 69,000 units per year, about twice the overall long-term average (2000-2015).

Furthermore, for long-distance commuters seeking to purchase homes in development fringe areas, the levels of new single-family homes in these areas were about triple their long-term average levels. Development fringe areas include Palmdale/Lancaster, Victorville/Hesperia and Moreno Valley/Perris.

Consequences of Unrealistic Economic Returns: Since the Southern California housing price bubble imploded in 2007, new home activity declined by more than 67 percent from 2009-2012, but has recently recovered to about -38 percent, as compared to its long-term average.

By comparison, for the development fringe areas, the level of single-family activity declined by 71 percent during 2008-2010 and declined even further by 85 percent during 2011-2014, due to high levels of foreclosures and short sales. Since only a modest improvement is expected in 2015, the overhang of the enormous supply created during 2003-2005 has effectively produced a housing recession that has lasted some eight years so far! (See Figure 18.)

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Conditions in the economy such as employment levels and financial/mortgage rates are primarily determined by national and global macroeconomic factors. However, regional/local public agencies may consider potential policies that affect the geographical distribution of housing, including long-distance commuters, which may alleviate further increases in traffic congestion.

- Economic Return Under �Stable� Conditions

First, consider policies that may influence the �benefit side� by offering more attractive housing within the urban setting that provides a substitute for single-family homes, such as planned developments with �detached� homes on smaller size lots complemented with parks/amenities.

Secondly, consider policies that may influence the �cost side� such as higher gas taxes or some types of freeway usage fees. However, it is important to note that such policies are quite complex to equitably implement. - Economic Return Under �Robust� Conditions

Policy attempts to influence long-distance commuters under robust economic conditions, recognizing that households are entitled to make their own decisions, should include providing them with additional information so that their decisions consider subsequent market corrections. Potential reductions in long-distance commuters that make more educated decisions in robust housing market conditions would reduce congestion. Further, by reducing the amount of new home activity in development fringe areas, the depth of a subsequent recession may be mitigated.

Figure 18: Relative Levels of New Single-Family Development Activity

Southern California Overall vs. Development Fringe

Joe Janczyk, a member of Treasurer John Chiang’s Council of Economic Advisors, is president of Empire Economics. The opinions in this article are presented in the spirit of spurring discussion and reflect those of the author and not necessarily the Treasurer, his office or the State of California.