Guest Column: Much Ado About the Federal Funds Rate (FFR)

By Christopher Thornberg

It finally happened. The Federal Reserve decided to raise the Federal Funds Rate by a quarter of a percent at their December meeting. Given the massive coverage of the decision and the hyperbolic rhetoric surrounding the change you might think that this is some true turning point in US economic history. Not really. Indeed we might argue that this is largely a non-story for the vast majority of Americans.

The FFR, which is at the center of Fed interest rate policy, is an obscure number that relates to the cost of lending between banks within the Federal Reserve accounts on an overnight basis. It is not a rate that businesses or households will actually ever see on a bill or loan payment slip. The rates we do care about�mortgage rates, the prime rate, etc.�are actually set by market forces, not by the Federal Reserve.

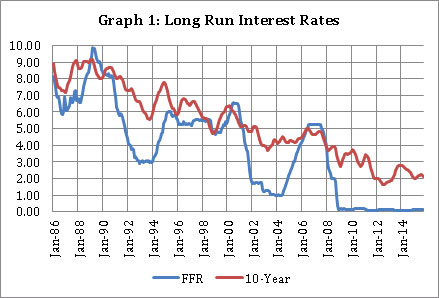

This isn�t to say the FFR doesn�t have some impact on all these other rates, but the connection is far more obtuse than many realize. The graph below shows the history of interest rates for the 10-year treasury (the core driver of mortgage rates) and for the FFR. Both have been trending down over the past three decades. We can also see the cyclical aspects of the data�times when the Fed works to cool what it perceives as an overheated economy (FFR rises sharply) or tries to stimulate a sagging one (FFR declines sharply).

If you squint, you can see the �spillover� from the FFR into the 10-year treasury rate. But it�s clear that the impact is nowhere close to one-to-one. To get a sense of how significant the pass-through is, the following table shows what happens to the FFR between policy turning points (when rates begin to rise or fall suddenly) and how the 10-year and 5-year treasury responds.

Over the last three cycles the Fed has tightened the FFR by an average of slightly over 3 percentage points. The average jump in the 10-year Treasury for these increases was only six-tenths of a percent. Some of this has to do with the downward trends in the data. If we include periods when the FFR is falling, a 4 percentage point shift in the FFR leads to about a 1 percentage point change in the 10-year�a 1 to 4 pass through. The 5-year treasury is a bit more impacted, but the pass through is still much less than 2 to 1.

Table 1: Pass Through Effects 1985 to 2010

| Federal Funds Rate Change | 10-Year Rate Change | 5-Year Rate Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trough to Peak | Average | 3.37 | 0.61 | 1.27 |

| Peak to Trough | Average | -4.86 | -1.56 | -2.37 |

What it all means is that even if the Fed starts to move rates sharply, there will only be small effects on other rates. If the Fed moves the FFR a full percentage point over the next year, this will increase 10-year treasuries by .25 percentage points and 5-year treasuries by .45 percentage points. This is not going to ramp up earnings on bond portfolios or have a significant impact on the housing market�the changes are simply too small.

But what if the Fed raises the FFR by 4 points or more? Well, it won�t. Indeed, it can�t. There is a functional limit on how far rates can go up. If the Fed pushes the FFR way above long-term rates it creates what economists refer to as an inverted yield curve, which is very tough on bank financials and can slow lending sharply. Extremely aggressive maneuvers are only used when the Fed feels the economy is really overheated�as it did in 2006, 2000, and 1989. And even in those cases, the Fed didn�t move the FFR much above long-term rates.

So if the Fed thinks the markets are truly overheated, it will still only raise rates 2.5 percentage points, which would push 10-year treasuries up by .6 percentage points. This leaves mortgage rates well under 5%, very low relative to the last 30 years.

But the Fed doesn�t think the economy is overheated, nor should it. With Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth still below 3%, stagnant wage growth, inflation well below the target of 2%, and lending growth that is still subdued, it would think the opposite. This means small moves�which means even smaller changes in the rates you and I care about.

So why does the market care so much? Because people in the market think that other people in the market believe that still other people in the market do care. And in the big game known as market trading this means largely irrelevant things can take on a preposterously huge role in the media.

Christopher Thornberg is a member of Treasurer John Chiang’s Council of Economic Advisors. The opinions in this article are presented in the spirit of spurring discussion and reflect those of the authors and not necessarily the Treasurer, his office or the State of California.